by Alexis Petridis, The Guardian, Friday 27 February 2009

For his new CD, Norman Cook concocted a fictional supergroup with Iggy Pop, David Byrne and Martha Wainwright. He tells Alexis Petridis about his free-form – and free-flowing – approach

In Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain’s epic history of American punk, Please Kill Me, Iggy Pop protests that his memory fails him when it comes to his activities in the 70s, an inevitable side effect of his legendary personal regimen during the era: "I didn’t go home at night and write this stuff down, like, ‘Dear Diary …’" he says. He certainly seems to be having difficulty remembering a story from the mid-70s now. "I think," he drawls, down the phone from Miami, "I’d shot some very bad skag and woke up in a bedsit in a rather undistinguished neighbourhood, with no idea how to get back to W1. I was looking for a tube entrance, rather stumbling and struggling and I met some chaps who told me they had some sort of group called the Brighton Port Authority. I may have sung for them for subway fare. I know I’ve never gotten a fucking penny from it. I think one of them was the guy from the Housemartins, but I don’t remember much more about it."

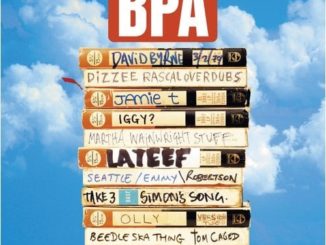

This time, however, the problem is less his Herculean drug intake of the time than the fact that he’s making up the story on the spot. If you believe the advance publicity, the Brighton Port Authority’s album, I Think We’re Gonna Need a Bigger Boat, is a collection of previously unheard recordings by a mythic Brighton musical collective that existed between the early 1970s and early 90s, and boasted a selection of special guests ranging from Iggy to Martha Wainwright to Dizzee Rascal to David Byrne. But you shouldn’t believe the advance publicity. The BPA’s debut album is a collection of collaborations between Norman Cook and various friends, recorded in Cook’s home studio and then "completely forgotten about".

"I’d find myself looking at tape boxes," says Cook, "going, ‘Martha Wainwright? I did a tune with her?’ She couldn’t remember it either. You know, time passes, alcohol was involved. It’s all a bit sketchy."

The story of the BPA was made up to cover "the bits we don’t remember", says Cook. But, sitting in the living room of what Iggy Pop describes, not inaccurately, as his "very English, very understated palatial pad", he seems unsure whether to keep up the pretence. On the one hand, influenced by his friend Damon Albarn’s Gorillaz project, he has put a lot of effort into constructing the BPA story – there are fake BPA photos and flyers for a gig with the Clash and Roxy Music, and YouTube films. On the other, Cook seems almost pathologically predisposed to tell the truth in interviews: as he has often noted, his candour, not least on the subject of his enthusiasm for drugs, became something of a problem when he married TV presenter Zoë Ball.

In any case, the true story of how he actually encountered Iggy Pop isn’t much less exotic than the official version. They met while Cook was DJing in Miami, "in one of these really silly clubs to which I want you to understand I never go", chuckles Iggy Pop. "I’m not an aficionado of boom-tish-boom-tish-boom-tish music, but I was single at the time and I heard a lot of chicks go to these places." He has a long and complicated story about being taken there by an out-of-work Las Vegas stripper and a starstruck French girl ("’Mon Dieu!’ she said. ‘It’s Iggy Pop! Sacré bleu!’") who attempted to impress him with her chemical arsenal: "She opened up the double breast of her trenchcoat and she had the entire inside lined with specially designed drug pockets. It was like a tradesman’s toolkit. She had it all! That scared me, so I ended up just listening to Norman in his Hawaiian shirt."

For his part, Cook says their friendship swiftly became physical: "I gave him a big hug, and the next thing I know, there’s tongues involved. The next day, I phoned up Zoë and went, ‘I snogged Iggy Pop on stage last night’. It’s that kind of relationship we’ve had for a long time."

And, as seems to be the case with everyone who makes Cook’s acquaintance, Iggy Pop eventually ended up as a house guest in Hove. ("The weird thing is," Cook recalls, "he’ll tell you all these tales about doing smack and that, but he’s the perfect guest, very quiet and polite.") And, as seems to be the case with everyone who ends up as a house guest in Hove, Iggy wound up drunk, in the recording studio next to the living room: "Most people are into doing it, but sometimes I have to give them Rohypnol and drag them in there," Cook guffaws, "and date-tape them."

Now well into his 40s, Cook remains a firm believer in working while under the influence. Fatboy Slim’s greatest hits were famously recorded on Sunday evenings, after a weekend of partying, "to avoid the comedown". For the benefit of anyone who might doubt the efficacy of such a working method, Cook is keen to point out that in a period of about three weeks, he came up with every one of the tracks that made him a household name: "Rockafeller Skank, Praise You, Right Here Right Now, the remixes of Brimful of Asha and Renegade Master by Wildchild. It was like bam-bam-bam, like lightning striking, I was on fire. I still hear those songs all the time, and in the right environments. I was watching the Superbowl the other night and the teams came out to Right Here Right Now. You know, it’s not like I did a tune about dogs and so when there’s a thing about a lost dog on the local news it always gets played in the background."

Perhaps understandably, he sees no reason to take recording sessions more seriously now. "A whole part of the process is being freed up from constraints, and here there’s no constraints whatsoever, apart from the fact that at some point, everybody has to go home. It’s nice to go a bit free-form. It stops you thinking, ‘Oh God, it’s me and Martha Wainwright, or me and Iggy Pop, what will people’s expectations be?’"

Nevertheless, there are drawbacks to this approach. "You do end up with quite a lot of twaddle, a lot of self-indulgent ranting, extended jams." These have been ruthlessly excised from the BPA album: whatever accusations you may want to throw at Norman Cook, you could never accuse him of musical self-indulgence or lacking a keen pop sensibility. He has recently been playing a homemade remix of Arcade Fire’s No Cars Go, he says: "It was Zoë’s idea, but I thought it sounded a bit like Big Country or something, so I took all the boring bits out." By boring bits, Cook means everything except the song’s chorus.

You could argue that’s a wilfully shallow approach to music, although it’s worth noting that Cook credits his longevity as a DJ and producer to a certain wilful shallowness. For someone who’s managed to translate his fabled affability into an entire album, Cook cuts an oddly solitary figure in Dom Phillips’s new history of 90s dance music, Superstar DJs: Here We Go! – not least because he’s the only one of the superstar DJs who still seems to be enjoying himself, in contrast with, say, Radio 1’s leathery king of dance Pete Tong, still joylessly playing the clubs at nearly 50, even though he considers DJing "the ultimate glorified manual labour". Cook seems to have emerged from the druggy hubris and chaos detailed in Phillips’s book with not just his career, but also his dignity, intact.

His eyes narrow a bit at the mention of the word "dignity". "I agree with you that I’m still enjoying it, but I think it’s because I never did it with dignity. I think the superstar DJs who have fallen from grace are the ones who thought that there was dignity in what they were doing, perhaps took themselves seriously just for a second. We’re not artists. We’re not creating art, we’re creating a party. You have to remember it’s all about the party, it’s not about you. If you don’t take yourself seriously, there’s nowhere to fall." Other DJs used to get "really pissed off" about his self-effacing attitude, he says, not least when he told a journalist that "a monkey" could make his records. "I remember Tom and Ed from the Chemical Brothers going, ‘Actually, we really believe in what we do.’ Well, I believe in what I do, but the art of it is not to believe that it’s anything more than what it is."

Accordingly, getting Cook to admit to any kind of serious intent behind his music is a tricky task. Nevertheless, there does seem to be something a little more weighty behind the BPA and its attendant story than just a record of a drunk producer mucking about with his famous friends and making stuff up for the press. The last Fatboy Slim album, 2004’s Palookaville, sold substantially fewer copies than its multi-platinum predecessors. Cook thinks that might be because "a lot of Palookaville was quite obscure, at least by my standards. It was as close as Fatboy Slim would ever come to Kid A." He laughs uproariously. "Which is obviously not that close." The truth may be that it sounded like an album made by a man who was sick of being Fatboy Slim, at least in the studio. The best moments were those that least resembled his earlier work.

Today, he is at pains to point out that he’s not retiring the Fatboy Slim name that keeps selling out beach parties around the world, but admits he has enjoyed working "outside the confines of club music", creating a new pseudonym to add to his lengthy collection: Pizzaman, the Mighty Dub Kats, Fried Funk Food, Freakpower. "There is a chance that Fatboy Slim might not make any more records," he says carefully, "but as a DJ, I’m doing bigger and bigger shows and having more and more fun. Rumours of Fatboy Slim’s demise have been exaggerated." He reels off a list of parties Fatboy Slim is set to play in Japan, Australia, eastern Europe. "There are times when I think, ‘Please make it stop.’ I know it seems like the best thing in the world, and I know I wanted it all my life, but there’s no off switch."

Actually, he says, that’s one of the good things about Palookaville’s relative commercial failure. "I was quite happy to take my foot off the gas for a bit. And the tabloids leave us alone now. I came out of Radio 1 yesterday and there was a paparazzo, and he looked at me as if to say, ‘Yeah, I know who you are and I’m not going to even bother raising my camera,’ which was really nice, really liberating." He grins. "I’m very happy that some people don’t give a toss any more."

source: www.guardian.co.uk

Be the first to comment