Nicholas | |

|---|---|

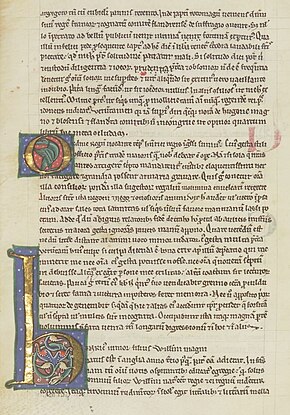

The crypt of Worcester Cathedral, one of the few surviving parts of the building which date to Nicholas's time | |

| Diocese | Worcester |

| Elected | c. 1116 |

| Predecessor | Thomas |

| Successor | Warin |

| Personal details | |

| Died | 24 June 1124 |

Nicholas of Worcester (died 24 June 1124) was prior of the Benedictine priory of Worcester Cathedral from about 1115 until his death. He was born around the time of the Norman Conquest. It is not known who his parents were, but the twelfth-century historian William of Malmesbury wrote that he was "of exalted descent",[1] and the historian Emma Mason argues that he was a son of King Harold Godwinson.

Nicholas was the favourite pupil of Wulfstan, the Bishop of Worcester, who brought him up. Wulfstan, the last surviving Anglo-Saxon bishop, lived until 1095. He was influential in transmitting Old English culture to Anglo-Norman England. Nicholas carried on this work as prior, and he was highly respected by the leading chroniclers, William of Malmesbury, John of Worcester and Eadmer, who acknowledged his assistance in their histories. Several letters to and from Nicholas survive.

Nicholas was an English monk at a time when both Englishmen and monks rarely received promotion in the church. When Bishop Theulf of Worcester died in October 1123, Nicholas led an unsuccessful attempt of the monks of the priory chapter to be allowed to choose the next bishop.

Background

In the late 960s, Oswald, Bishop of Worcester and one of the leaders of the late tenth-century English Benedictine Reform, set up Worcester Cathedral priory as a Benedictine monastery.[2] Almost a century later, in 1060, Ealdred, Bishop of Worcester, was appointed Archbishop of York, and he attempted to revive the practice of some of his predecessors (including Oswald) of holding York and Worcester in plurality. However, Pope Nicholas II forced him to relinquish Worcester, and Wulfstan was appointed to the see in 1062, four years before the Norman Conquest. He lived until 1095 and was the last surviving Anglo-Saxon bishop.[3] The historian Emma Mason writes that Wulfstan "played an important role in the transmission of Old English cultural and religious values to the Anglo-Norman world".[4] He was regarded as a saint in his lifetime and was canonised in 1203.[5]

Family and early life

Nicholas's date of birth and parents are not known. He was brought up by Wulfstan, who was like a father to him.[6] In his Vita Wulfstani (Life of Wulfstan), the twelfth-century historian William of Malmesbury wrote: "On his English side, Nicholas was of exalted descent. His parents paid the holy man high respect, and won his friendship by the many services they did him. Wulfstan baptised Nicholas as a child, gave him a fine education in letters, and kept him continually at his side when he was old enough."[1] Mason suggests that William may not have named Nicholas's father out of discretion, because he was a member of a leading dynasty in the regime before the Norman Conquest. She argues that his most likely father was King Harold Godwinson, who was a close friend of Wulfstan and supported his election as bishop.[7] According to William of Malmesbury, Harold "had a particular liking for Wulfstan, to such a degree that in the course of a journey he was ready to go thirty miles out of his way to remove, by a talk with Wulfstan, the load of anxieties oppressing him".[8] Wulfstan was loyal to kings from Edward the Confessor to William II, but Harold was the only king whose devotion to Wulfstan was emphasised by William of Malmesbury.[9] Mason suggests that Nicholas was Harold's son by Ealdgyth, who married Harold in or after 1063. She was a daughter of Ælfgar, Earl of Mercia, a member of the other great dynasty of the period.[a] After 1066, the Godwin properties were forfeit and members of the family had poor secular prospects, so life as a Benedictine monk was a much better alternative.[12]

The historian Eadmer, who was a friend of Nicholas, mentions as one of his sources for his Life of Dunstan, an Æthelred who was sub-prior of Canterbury and later a dignitary of the Worcester church.[13] In 1928 the scholar Reginald Darlington suggested that Æthelred and Nicholas were the same man.[14] Mason gave a detailed defence of the theory in 1990: Nicholas was not an Anglo-Saxon name, but by the late eleventh century it was becoming common for recruits to monastic life to be given a new name in religion, and he may have been named after Pope Nicholas II, whose refusal to allow York and Worcester to be held in plurality paved the way for Wulfstan's appointment.[15] The identification of Nicholas with Æthelred is also accepted by the medievalists Ann Williams and Patrick Wormald,[16] but the theory is disputed by the historian of religion David Knowles because Eadmer stated that Æthelred had earlier served for a long time under Bishop Æthelric of Selsey, who died in 1038, and Nicholas would have been too young for the association with Æthelric and a senior position at Canterbury.[17][b]

In his Vita Wulfstani, William of Malmesbury describes an incident that illustrates Wulfstan's affection for Nicholas. On one occasion when he was stroking the young man's head, Nicholas jokingly thanked Wulfstan for trying to save his hair, which was receding. Wulfstan replied that he would not go bald so long as Wulfstan lived. Nicholas lost his remaining hair around the time that Wulfstan died, and Mason comments that whereas the modern reader would see progressive baldness, the twelfth century saw the success of a minor prophecy.[20][c]

Life

Monk

Nicholas was a devoted disciple of Wulfstan,[22] and was described by William of Malmesbury as "his revered pupil", and "his particular favourite among his pupils".[23] To complete Nicholas's training, Wulfstan sent him off to Lanfranc, the Archbishop of Canterbury between 1070 and 1089. The usual way of spreading reforms among monasteries was to invite them to send a young monk to the originating house to learn the new customs.[24] Nicholas probably brought back parts of Lanfranc's Monastic Constitutions, which regulated the daily routine of Canterbury monks.[25] One of the changes in religious observance at Worcester was the introduction of feasts of the Blessed Virgin, and Nicholas may have brought them from Canterbury.[26]

The historians Emma Mason and Julia Barrow suggest that Nicholas was probably involved in the production of the fraudulent Altitonantis, which purported to be a contemporary record of the establishment of monasticism at Worcester by Oswald in the 960s.[27] Altitonantis is connected with a letter by Nicholas about the parentage of King Edward the Martyr (r. 975–978), as both documents incorrectly state that his father King Edgar vanquished the King of Dublin and both describe it by the same word, subiugare (subjugate).[28] Mason wrote that: "Nicholas, in his later years, wrote persuasively in defence of the interests of his monastic community, and was fully aware of the importance of preserving documentation to support his case".[29]

In Mason's view, Wulfstan probably authorised the production of Altitonantis in order to support legal claims by the monastic community for which they had no genuine documentary evidence. In that period, forgery by monks in defence of the church was regarded as acceptable.[30] The monks of Canterbury carried out a programme of forgery in the 1070s purporting to show that privileges claimed for the archbishopric had an ancient origin, and Mason comments that Nicholas may have brought back from his stay there "innovative, not to say imaginative, techniques in the drafting of charters".[31] On the other hand, Barrow dates Altitonantis to the episcopacy of Wulfstan's non-monastic successor, Samson, who replaced the monks of Westbury Priory with secular (non-monastic) canons, probably making the Worcester priory monks fear the same fate. Worcester had only become solely monastic after Oswald's death, but Altitonantis claimed that he had driven out the secular clerics, justifying Worcester's exclusively monastic status by bringing its history in line with the expulsion of secular clergy from Winchester Cathedral in 964.[32]

Prior

Nicholas later became prior of Worcester, its head under the bishop. Prior Thomas died in October 1113 and no other prior is known before August 1116, when Nicholas is recorded as holding the office.[33] The historian Richard Southern dates Nicholas's appointment to 1113, and this date has been widely accepted by other scholars.[34] However, William of Malmesbury stated that Nicholas was appointed prior by Bishop Theulf.[35] Bishop Samson of Worcester had died on 5 May 1112, and King Henry I nominated Theulf as his successor on 28 December 1113, but as the archbishopric of Canterbury was then vacant he was not consecrated until 27 June 1115, when Archbishop Ralph d'Escures received his pallium from Rome and was thus empowered to perform the ceremony.[36] The scholars Michael Winterbottom and Rodney Thomson date Theulf's tenure as 1115 to 1123, and Nicholas's appointment to c. 1116.[37]

According to William of Malmesbury, Bishop Theulf later turned against Nicholas. William wrote:

- [Theulf] had once seemed quite moderate. He spoke kindly to his monks, and took the responsibility of appointing one of them to be prior, a man of high learning. But later he so harried him that he had neither horse nor furniture left that Theulf did not get out of him either by prayer or by force. He insisted that the prior pay for the restoration of the church after a fire, though bishops had always patched the place up out of their own resources as a matter of course. In the end, after expelling one or two monks, he went so far as to think of demoting the prior himself. But the judgement of God forestalled man's temerity. On the very day that Theulf had been going to act, his corpse was being bewailed at his vill.[38]

Wulfstan's long survival after the Norman Conquest allowed him to inculcate the values of English monasticism into the first wave of French monks in Worcester, and his work was carried on by Nicholas during his time as prior.[39] The Monastic Constitutions gave considerable independent power to the prior,[40] and William of Malmesbury wrote that, as prior, Nicholas "in a short period gave many proofs of his hard work. And, something I think particularly to his credit, he so inculcated letters into the occupants of the place, by both teaching and example, that, though they may be inferior in numbers, they are not surpassed in zeal for study by the highest churches of England."[41] Mason comments: "The sensitive disciple glimpsed in the Life of Wulfstan matured into an effective prior. Given the prejudice against Englishmen in high office by the twelfth century, it is a reflection of the impact which Wulfstan himself had upon the chapter that his protégé could succeed to this office in the second decade of the reign of Henry I."[42] Eadmer complained about this prejudice, stating that English nationality debarred a man from achieving high office in the church, however worthy he was.[43]

Manuscript production in most of England declined sharply immediately after the Conquest and revived at the end of the century, but Worcester was an exception to this pattern. There was no post-Conquest decline, but the choice of books was conservative and most were written in Old English. Production declined between around 1090 and 1110, but it revived thereafter and by the time of Nicholas's priorship it had returned to its previous level. There appears to have been a complete turnover in scribes as no hand in late eleventh century manuscripts is found in early twelfth century ones. The twelfth century revival saw almost all books in Latin and integration into the contemporary literary culture.[44]

Assistance to historians

Two leading monastic historians, William of Malmesbury and Eadmer of Canterbury, paid tribute to the help they received from Nicholas.[22] Nicholas kept up close connections with the monks of Canterbury, including Eadmer.[45] They almost certainly met when Nicholas was sent to Canterbury as a young man, and they kept up a friendly correspondence almost until the end of Nicholas's life.[46]

Eadmer stated that he wrote his Vita S. Oswaldi (Life of St Oswald) and Miracula S. Oswaldi (Miracles of Oswald) at the request of his Worcester friends.[47] Southern suggests that the works "may possibly be connected with the election of Nicholas as prior in 1113",[45] and the scholars Andrew Turner and Bernard Muir state that the Vita and Miracula must have been completed before 1116.[48] On the basis of these points, a date for the works of 1113 to 1116 is widely accepted by scholars.[49] The historian William Smoot argues that Eadmer was chosen in order to enhance Worcester's spiritual prestige by associating it with that of Canterbury.[50]

Nicholas also assisted Eadmer with his Life of Dunstan, who had been appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by King Edgar. The hagiographer Osbern had written that Edgar fathered his eldest son, Edward the Martyr, by seducing a nun, and Eadmer was anxious to disprove the allegation. He appealed for help to Nicholas, who consulted ancient vernacular chronicles and stories, together with other unspecified sources, and sent a reply that Eadmer adopted in the Life. Nicholas wrote that Edward was the son of Edgar's lawful wife Æthelflæd, daughter of Ordmær, ealdorman of the East Angles.[51] Most historians accept that Nicholas is correct on Edward's parentage, although they think that he got Ordmær's status wrong as there was no ealdorman with that name.[52] However, Williams suggests that Nicholas invented Æthelflæd in order to absolve Edgar from the charge of carnal knowledge of a nun.[53] Historians are puzzled that Edgar is not known to have been crowned until 973, fourteen years after his accession. It is thought likely that there was an earlier unrecorded coronation,[54] but Nicholas wrote that Edgar delayed out of "piety ... until he might be capable of controlling and overcoming the lustful urges of youth". Janet Nelson comments: "Well, if that took Edgar until he was nearly thirty, he must have been – for those days – a late developer!"[55]

A biography of Wulfstan in Old English by his chaplain Coleman was criticised by his fellow monks for the inclusion of fabricated miracle stories. William of Malmesbury translated it into Latin, but added information given to him by Nicholas, whose contribution included anecdotes illustrating Wulfstan's spirituality.[56] William quoted Nicholas as saying that Wulfstan was "versatile and sedulous in his prayers".[57] William was not impressed with Coleman's overblown prose, and he would have preferred a life by Nicholas: "Nicholas loved to tell over the doings and sayings of Wulfstan, and could perhaps be criticised for not writing his biography. For no one could have more truthfully recorded a life that that no one knew more intimately at first-hand."[58] One story is about Nicholas himself. When arguments among Wulfstan's hired knights threatened to lead to fighting,[d] he banned all alcohol for the day. Nicholas was the one person who dared to defy the order, taking advantage of his privileged status. But he felt so guilty about his transgression that when he went to sleep he was plagued by repeated nightmares, and finally realised that the only way to stop them was to confess to Wulfstan and ask for pardon, which he did and was granted forgiveness.[60]

In 1120 Eadmer was nominated as Bishop of St Andrews, and he faced demands by King Alexander I of Scotland and the canons of York that he should do obedience to York rather than Canterbury. Nicholas supplied him with a considerable body of historical evidence to disprove the arguments for York. The historian Martin Brett comments that Nicholas gave him "excellent advice on his future conduct", and that this letter and the one on Edward the Martyr "display a wide historical learning". Eadmer was forced to resign within six months.[61]

The wide circulation of John of Worcester's Chronicle was partly due to Worcester's reputation as a cultural centre, and Nicholas was critical to its cultural connections.[62] Wormald comments:

- One of the things that is increasingly clear about twelfth-century Worcester is the special effort that it put into the reconstruction of the Anglo-Saxon past. One of its fruits was precisely John of Worcester's Chronicle. Such was its reputation for historical expertise that Eadmer, the Canterbury historian and biographer of Anselm, twice consulted Prior Nicholas of Worcester about historical issues. One of these was the rights of the metropolitan see of York in Scotland – about which one might have expected Eadmer to know enough already.[63]

Dispute over bishopric

Benedictine monks became dominant in the English church in the reign of King Edgar, but in the eleventh century an increasing number of bishops were secular clergy, especially royal clerks.[64] All Archbishops of Canterbury were monks (apart from Stigand) from Edgar's reign until the death of Ralph in 1122, but by this time almost all bishops were secular clergy, and most were former clerks of the royal chapel.[65] The monks came under increasing attack in the early 1120s, with the struggle mainly centring on the elections to Canterbury in 1123 and Worcester in 1124.[66] In both dioceses election was formally by the monks in their chapter, but in practice they had to submit to the king. In 1123 the bishops were determined not to have another monk as archbishop, and the king took their side. Although the monks were given a choice, it was between four secular clergy, and they selected William de Corbeil, an Austin canon.[67]

When Bishop Theulf died on 20 October 1123, Eadmer sent a letter to Nicholas and his monks described by the historian Denis Bethell as "decidedly hysterical in tone": "Oh, my dearest friends, I beg you, I beg you ... Think in how much envy the monastic order now stands of evil intentioned men, and how they plot to remove it from the bishoprics".[68] Nicholas used all his learning and literary skills to lead a campaign of the Worcester chapter to secure a free election.[42] He wrote to Archbishop William asking him to "take us under your wings as chickens under the feathers", and went on:

- And because the King and all the other princes of the realm have a special love towards you, and will listen to you attentively, we beg that you may persuade him by your letters and by citations from canon law, to grant us a free and canonical election of our bishop, lest our church, which has hitherto been protected by pious and modest pastors, should be handed over to an alien and a tyrant. And if, which God forbid, the King should dare to deny us this, your authority will not hesitate to go against him with the sword of canonical rigour. For He, who protected the audacity of St Peter when he cut off Malchus' ear amidst the soldiers, He also has reserved something to St Peter's successors.[68]

William's reply was unhelpful, exhorting the monks to piety and not mentioning the election. Nicholas also wrote to William Giffard, Bishop of Winchester, appealing to him "so to manage things with the king that he may concede us a free and legal faculty for the election of a bishop according to canon law". Bethell describes this request as "extraordinary" because no previous bishop had been so elected and Theulf had purchased the see by bribery.[69] Mason comments that "Wulfstan would have approved of his protégé's aims, even though his methods reflected nothing of the bishop's reputed simplicity".[42] Nicholas's death in June 1124 left the proponents of a free election leaderless, and the monks had to accept Queen Adeliza's chancellor, Simon, who was ordained a priest on 17 May 1125 and consecrated as Bishop of Worcester the next day.[70]

Nicholas's campaign for canonical selection was a new departure, as there had been no interest previously in England in the process of election. But Rome was increasingly opposing lay control over episcopal appointments, and Pope Callixtus II had come close to quashing the election of William de Corbeil partly on the ground that the Canterbury electors had been unwilling to accept him. This was almost certainly why the monks of Worcester thought that they might be able to secure a free election. From 1125 the fortunes of the monks revived, and they filled around half of the episcopal vacancies over the next thirty years.[71]

Death

Nicholas's death is only recorded by John of Worcester, who wrote in his entry for 1124: "The revered prior of Worcester, Nicholas, died on Tuesday, 24 June. May he rejoice in heaven through the mercy of God!"[72] He was succeeded as prior by Warin.[39]

Letters to and from Nicholas

Letters to and from Nicholas are in two manuscripts. Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 371 is the personal manuscript of Eadmer.[73] MS Cotton Claudius A I folios 34–37 verso is a dossier made by someone concerned with the Canterbury interest in episcopal elections. It resembles MS Cotton Vespasian E IV folios 203–210, which contains letters with Worcester connections, and both may have been personal dossiers of Nicholas.[74] All letters are in Latin.

- From Nicholas to Eadmer on the mother of Edward the Martyr, Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 371, pp. 6–7,[75] printed in (1) William Stubbs, Memorials[76] and (2) Martin Rule, Eadmeri.[77]

- From Nicholas to Eadmer on the claim of the archbishopric of York to primacy over the Scottish Church, Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, 1120, MS 371, pp. 7–9,[75] printed in (1) Henry Wharton, Anglia Sacra,[78] (2) Haddan & Stubbs, Councils and Ecclesiastical Documents,[79] and (3) Jacques Paul Migne, Patrologia Latina, volume clix, pp. 809–812.[75]

- From Eadmer, monk of Canterbury to the prior and community of Worcester, MS Cotton Claudius A I, folio 36v, printed in (1) Wharton, Anglia Sacra,[80] (2) Migne, Patrologia Latina, volume clix, p. 807 and (3) Bethell, "English Black Monks".[81]

- From the prior and community of Worcester to William, Archbishop of Canterbury, MS Cotton Claudius A I, folio 36r, printed in Bethell, "English Black Monks".[82]

- From William, Archbishop of Canterbury to the prior and community of Worcester, MS Cotton Claudius A I, folio 36v, printed in Bethell, "English Black Monks".[83]

- From Nicholas to William Giffard, Bishop of Winchester, MS Cotton Claudius A I, folio 36r, printed in Bethell, "English Black Monks".[84]

Notes

- ^ Mason suggests that the family of Ælfgar provides alternative but less likely candidates for the father of Nicholas. Ælfgar also supported Wulfstan's election as bishop in 1062, but his family often seized lands of the Worcester church.[10] Ælfgar was an opponent of the Godwins who was twice exiled in 1055 and 1058. He is not heard of after 1062 and probably died in that year or shortly afterwards.[11]

- ^ Historians cite as evidence for the Æthelred theory that he is not included in a list of Worcester monks in the Durham Liber Vitae, but this dates to around 1105 and it also leaves out Wulfstan's chaplain and author of his Old English biography, Coleman.[18] Eadmer implies that Æthelred was long dead when the Life was written between 1105 and 1109.[19]

- ^ William gives a different version of this story in his Gesta Pontificum Anglorum.[21]

- ^ In 1085 King William I ordered all magnates to keep a force of knights as protection against a planned (but aborted) Danish invasion.[59]

Citations

- ^ a b Winterbottom & Thomson 2002, pp. 132–133 (iii. 17. 1).

- ^ Barrow 2014, p. 509; Blair 2005, p. 350; Mason 1998, p. 38.

- ^ Mason 2004b; Blair 2005, p. 350.

- ^ Mason 2004b.

- ^ Williams 1995, p. 148; Mason 1990, pp. 254, 280.

- ^ Mason 1990, pp. 219–221.

- ^ Mason 1990, p. 220; Brooks 2005, p. 7 and n. 24; Winterbottom & Thomson 2002, pp. 34–35 (i. 7. 3), 44–45 (i. 11. 2).

- ^ Winterbottom & Thomson 2002, pp. 34–35; Brooks 2005, p. 7 n. 24.

- ^ Brooks 2005, pp. 5, 7.

- ^ Mason 1990, p. 220.

- ^ Williams 2004.

- ^ Mason 1990, p. 221.

- ^ Turner & Muir 2006, pp. 46–47; Mason 1990, pp. 221–222.

- ^ Darlington 1928, p. xxxviii n. 2.

- ^ Mason 1990, pp. 221–222; Mason 2004a, p. 140.

- ^ Williams 1995, p. 168 n. 78; Wormald 2006, pp. 236, 246 n. 31.

- ^ Knowles 1963, p. 160 n. 7; Turner & Muir 2006, pp. lxxii, 46–47.

- ^ Mason 1990, p. 222 n. 108; Williams 1995, p. 168 n. 78; Knowles 1963, p. 160 n. 7; Tinti 2010, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Turner & Muir 2006, pp. lxvii, 46–47.

- ^ Mason 1990, p. 223; Winterbottom & Thomson 2002, pp. 132–133 (iii. 17. 2).

- ^ Winterbottom 2007, pp. 436–437 (iv. 147).

- ^ a b Mason 1990, p. 218.

- ^ Winterbottom 2007, pp. 436–437 (iv. 147); Winterbottom & Thomson 2002, pp. 132–133 (iii. 17. 1); Mason 1990, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Winterbottom & Thomson 2002, pp. 132–133 (iii. 17. 1); Mason 1990, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Mason 1998, p. 38.

- ^ Mason 1990, p. 130.

- ^ Mason 1990, pp. 216–217; Barrow 1992, p. 70.

- ^ Barrow 1992, p. 70.

- ^ Mason 1990, p. 217.

- ^ Mason 1990, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Mason 1990, p. 217; Mason 2004a, p. 197.

- ^ Barrow 2014, p. 509; Barrow 1996, p. 98; Knowles 1963, p. 41; Bateson & Costambeys 2004.

- ^ Mason 1990, p. 222; Mason 1998, p. 40.

- ^ Southern 1963, p. 283 n. 2; Gameson 2005, p. 62; Turner & Muir 2006, p. cvi; Brooks 2005, p. 5.

- ^ Winterbottom 2007, pp. 442–443 (iv. 151ß 2); Winterbottom & Thomson 2002, pp. 132–133 (iii. 17. 1).

- ^ Bateson & Costambeys 2004; Hoskin 2008.

- ^ Winterbottom & Thomson 2002, p. 132 nn. 2 and 3.

- ^ Winterbottom 2007, pp. 442–443 (iv. 151ß 2–3); Smoot 2020, pp. 369–370.

- ^ a b Mason 1990, p. 196.

- ^ Mason 1998, p. 40.

- ^ Winterbottom & Thomson 2002, pp. 132–133 (iii. 17. 1); Mason 1990, p. 196.

- ^ a b c Mason 1990, p. 224.

- ^ Williams 1995, p. 168.

- ^ Gameson 2005, pp. 61–62, 67–70.

- ^ a b Southern 1963, p. 283 n. 2.

- ^ Turner & Muir 2006, pp. xv–xvi.

- ^ Raine 1886, pp. 1, 59.

- ^ Turner & Muir 2006, p. cvi.

- ^ Smoot 2020, p. 355 and n. 7.

- ^ Smoot 2020, p. 357.

- ^ Williams 2003, p. 3; Stubbs 1874, pp. 422–424; Turner & Muir 2006, pp. lxxii, 136–137.

- ^ Nelson 1977, p. 67 n. 101; Roach 2016, p. 43; Yorke 2008, p. 144.

- ^ Williams 2003, p. 6.

- ^ Keynes 2008, p. 48.

- ^ Nelson 1977, p. 64.

- ^ Brooks 2005, pp. 4–5; Mason 1990, pp. 219, 271; Winterbottom & Thomson 2002, pp. 118–123 (iii. 9–10), 126–127 (iii. 13).

- ^ Winterbottom & Thomson 2002, pp. 118–119 (iii. 9. 2).

- ^ Orchard 2005, pp. 45–46; Winterbottom & Thomson 2002, pp. 132–133 (iii. 17. 2).

- ^ Bates 2016, pp. 457–458.

- ^ Winterbottom & Thomson 2002, pp. 130–133 (iii. 16); Mason 1990, p. 219.

- ^ Brett 1981, p. 113 and n. 1; Gransden 1992, p. 15.

- ^ Gransden 1992, p. 120.

- ^ Wormald 2006, p. 236.

- ^ Bethell 1969, pp. 673, 686.

- ^ Hollister 2001, p. 288; Bethell 1969, pp. 674, 686.

- ^ Bethell 1969, p. 673.

- ^ Bethell 1969, pp. 673–676, 681; Hollister 2001, p. 288.

- ^ a b Bethell 1969, p. 681.

- ^ Bethell 1969, pp. 682–683.

- ^ Bethell 1969, pp. 683–684.

- ^ Bethell 1969, pp. 678–679, 685–687.

- ^ McGurk 1998, pp. 156–157 and n. 5.

- ^ Southern 1963, p. 367.

- ^ Bethell 1969, p. 694.

- ^ a b c Southern 1963, p. 369.

- ^ Stubbs 1874, pp. 422–424.

- ^ Rule 1884, pp. cxxvi–cxxvii.

- ^ Wharton 1691, pp. 234–236.

- ^ Haddan & Stubbs 1873, pp. 202–204.

- ^ Wharton 1691, p. 238.

- ^ Bethell 1969, pp. 697–698.

- ^ Bethell 1969, pp. 695–696.

- ^ Bethell 1969, pp. 696–697.

- ^ Bethell 1969, p. 696.

Sources

- Barrow, Julia (1992). "How the Twelfth-Century Monks of Worcester Perceived their Past". In Magdalino, Paul (ed.). The Perceptions of the Past in Twelfth-Century Europe. London, UK: The Hambledon Press. pp. 53–74. ISBN 978-1-85285-066-1.

- Barrow, Julia (1996). "The Community of Worcester, 961–c.1100". In Brooks, Nicholas; Cubitt, Catherine (eds.). St Oswald of Worcester: Life and Influence. London, UK: Leicester University Press. pp. 84–99. ISBN 978-0-7185-0003-0.

- Barrow, Julia (2014). "Worcester". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (2nd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell. pp. 508–510. ISBN 978-0-470-65632-7.

- Bates, David (2016). William the Conqueror. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-23416-9.

- Bateson, Mary; Costambeys, Marios (2004). "Samson (d. 1112)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24600. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Bethell, Denis (October 1969). "English Black Monks and Episcopal Elections in the 1120s". English Historical Review. 84 (333): 673–698. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXXIV.CCCXXXIII.673. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 563416.

- Blair, John (2005). The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921117-3.

- Brett, Martin (1981). "John of Worcester and his Contemporaries". In Davis, R. H. C.; Wallace-Hadrill, J. M. (eds.). The Writing of History in the Middle Ages. Essays Presented to Richard William Southern. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. pp. 101–126. ISBN 978-0-19-822556-0.

- Brooks, Nicholas (2005). "Introduction: How do we Know about St Wulfstan". In Barrow, Julia; Brooks, Nicholas (eds.). St Wulfstan and his World. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-0-7546-0802-8.

- Darlington, Reginald, ed. (1928). The Vita Wulfstani of William of Malmesbury (in Latin). London, UK: Royal Historical Society. OCLC 1034977.

- Gameson, Richard (2005). "St Wulfstan, the Library at Worcester and the Spirituality of the Medieval Book". In Barrow, Julia; Brooks, Nicholas (eds.). St Wulfstan and his World. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. pp. 60–104. ISBN 978-0-7546-0802-8.

- Gransden, Antonia (1992). Legends, Traditions and History in Medieval England. London, UK: The Hambledon Press. ISBN 978-1-85285-016-6.

- Haddan, Arthur; Stubbs, William, eds. (1873). Councils and Ecclesiastical Documents relating to Great Britain and Ireland (in Latin). Vol. II, Part I. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. OCLC 669112764.

- Hollister, C. Warren (2001). Henry I. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08858-8.

- Hoskin, Philippa (2008). "Theulf (d. 1123)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/95182. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Keynes, Simon (2008). "Edgar rex admirabilis". In Scragg, Donald (ed.). Edgar King of the English: New Interpretations. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. pp. 3–58. ISBN 978-1-84383-399-4.

- Knowles, David (1963). The Monastic Order in England: A History of its Development from the Times of St Dunstan to the Fourth Lateran Council 940–1216 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54808-3.

- Mason, Emma (1990). St Wulfstan of Worcester c.1008–1095. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-15041-1.

- Mason, Emma (May 1998). "Monastic Habits in Medieval Worcester". History Today. 48 (5): 37–43. ISSN 0018-2753.

- Mason, Emma (2004a). The House of Godwine: The History of a Dynasty. London, UK: Hambledon and London. ISBN 978-1-85285-389-1.

- Mason, Emma (2004b). "Wulfstan [St Wulfstan] (c. 1008–1095)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/30099. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- McGurk, Patrick, ed. (1998). The Chronicle of John of Worcester (in Latin and English). Vol. III. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820702-3.

- Nelson, Janet (1977). "Inauguration Rituals". In Sawyer, P. H.; Wood, I. N. (eds.). Early Medieval Kingship. Leeds, UK: School of History, University of Leeds. pp. 50–71. ISBN 978-0-906200-00-1.

- Orchard, Andy (2005). "Parallel Lives: Wulfstan, William, Coleman and Christ". In Barrow, Julia; Brooks, Nicholas (eds.). St Wulfstan and his World. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. pp. 39–57. ISBN 978-0-7546-0802-8.

- Raine, James, ed. (1886). "Vita Sancti Oswaldi Auctore Eadmero". The Historians of the Church of York and its Archbishops (in Latin). Vol. II. London, UK: Longman & Co. pp. 1–59. OCLC 500544964.

- Roach, Levi (2016). Æthelred the Unready. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-22972-1.

- Rule, Martin, ed. (1884). Eadmeri Historia Novorum in Anglia (in Latin). London, UK: Longman & Co. OCLC 758734413.

- Smoot, William (December 2020). "Sacred Memory and Monastic Friendship in Eadmer of Canterbury's Vita S. Oswaldi". Revue Bénédictine. 130 (2): 354–388. doi:10.1484/J.RB.5.121995. ISSN 0035-0893. S2CID 234537562.

- Southern, Richard (1963). Saint Anselm and his Biographer: A Study of Monastic Life and Thought 1059–c.1130. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-06532-0.

- Stubbs, William, ed. (1874). Memorials of St Dunstan Archbishop of Canterbury (in Latin). London, UK: Longman & Co. OCLC 474445858.

- Tinti, Francesca (2010). Sustaining Belief: The Church of Worcester from c.870 to c.1100. Farnham, UK: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-75-460902-5.

- Turner, Andrew; Muir, Bernard, eds. (2006). Eadmer of Canterbury: Lives and Miracles of Saints Oda, Dunstan and Oswald (in Latin and English). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925380-7.

- Wharton, Henry (1691). Anglis Sacra (in Latin). Vol. II. London, UK: Richard Chiswell. OCLC 3312688.

- Williams, Ann (1995). The English and the Norman Conquest. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-708-5.

- Williams, Ann (2003). Æthelred the Unready: The Ill-Counselled King. London, UK: Hambledon and London. ISBN 978-1-85285-382-2.

- Williams, Ann (2004). "Ælfgar, earl of Mercia (d. 1062?)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/178. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Winterbottom, Michael; Thomson, Rodney, eds. (2002). "Life of Wulfstan". William of Malmesbury: Saints' Lives (in Latin and English). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. pp. 1–155. ISBN 978-0-19-820709-2.

- Winterbottom, Michael, ed. (2007). William of Malmesbury: Gesta Pontificum Anglorum, The History of the English Bishops (in Latin and English). Vol. 1. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820770-2.

- Wormald, Patrick (2006). The Times of Bede. Maldon, UK: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-16655-9.

- Yorke, Barbara (2008). "The Women in Edgar's Life". In Scragg, Donald (ed.). Edgar King of the English, 595–975. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. pp. 143–157. ISBN 978-1-84383-928-6.